The day was important to me. This was my first vote.

When I walked towards my polling booth in Sector 11 in Chandigarh on April 10, I knew I lived in a time history books and period films of the future would try to depict. I lived in the midst of a revolution, at a time when the youth the world over are rising up, overthrowing governments, making history.

When I walked towards my polling booth in Sector 11 in Chandigarh on April 10, I knew I lived in a time history books and period films of the future would try to depict. I lived in the midst of a revolution, at a time when the youth the world over are rising up, overthrowing governments, making history.

I am that youth, part of that revolution.

When people speak about elections, they speak about youth disengagement. Disillusionment. Perhaps they haven’t met the new youth of India.

Look at the incredibly talented All India Bakchod mocking the Congress and the BJP on YouTube. Look at the Aam Aadmi Party memes. Look at the thousands, the tens of thousands, who consume, spread those messages.

We are the new youth. We are engaged. And today I would seal my engagement by casting my first vote, ever. It was my duty. My chance to change my nation.

My city of Chandigarh is an interesting place. A Union territory serving as capitals to two states, Punjab and Haryana, it is not your average Indian city.

It has the highest human development and gender development indexes in the country. The third highest per capita income. Ninety-seven per cent of its population is urban, and the literacy rate is high, 86.43 per cent, compared to the national average of 74.04. Two Bollywood actors and an ex-federal minister are contesting the elections, and who comes to power will be a reflection on the sentiments of the educated, urban, high-income segment of the Indian population.

The 800,000 people of Chandigarh are spread across 63 sectors. Each sector is allotted a voting station, with one or more polling booths, depending on the population density.

My own booth was at the Government High School in Sector 11. Before I started out at 11am, my mother had checked on the web site of the Chief Electoral Officer, Chandigarh to see if there was a long queue. There wasn’t.

I entered the school through a small side gate, along with three others voters – an elderly couple and a middle-aged man with a Blackberry glued to his ear. A policeman was at the entrance. Spotting the couple tempting gravity with every step, he signalled to someone inside. A man rushed out with two wheelchairs. I was surprised. I had certainly not expected it to be organised to this level.

I queued up with some 10 people. Sector 11 had been divided into two, with a polling booth for each division. I could see senior citizens given priority and taken up to the head of the line. Within 10 minutes, barely one page into my book, it was my turn.

My identity was verified by four government officials, who matched my face to the photo on my voter’s card. Before I entered the booth, a fifth rechecked my identity and marked my index finger with a semi-permanent black dye. I had waited for that mark for long.

I pulled a grey curtain shut behind me and stared at the machine in front. I had always imagined the voting machine to be like an ATM. It was, only smaller.

There were about 10 names on the machine. To my dismay, they were all in Hindi. While the symbols were in most cases sufficient to let the voter know which button to press, it would have been good to have the name of the party in English as well. My grandfather, for instance, could not read Hindi. He would have been confused.

I pressed the button I wanted to. I heard a ping, the kind you hear when you summon assistance at hotel receptions.

It was done.

When I walked out into the hot sun, I was a democratically engaged Indian. By pressing a small button, I helped determine the course of India, and, to some extent, that of the world. I helped determine whether India will be a Communist nation, or whether it will follow a capitalistic model fuelled by trade and industrialisation. I determined whether equal rights will be granted to the LGBTQ community, whether sectarian policies will rage.

I took a stand on issues that matter to me — to us — today. I exercised my right to take that stand, and I am proud of it.

That is why I want to hold on to that black stain on my finger for as long as I can.

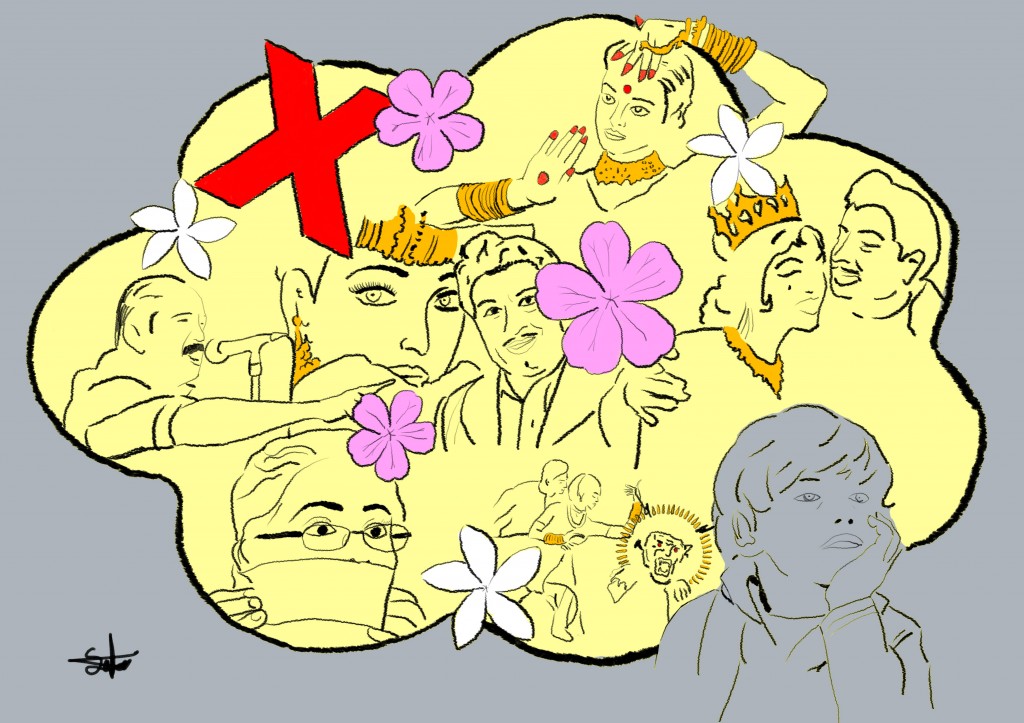

Image: Nabarun

This story was also published on Rediff.com, our media partner.