Author: Saba Sodhi

The day I helped change India

The day was important to me. This was my first vote.

When I walked towards my polling booth in Sector 11 in Chandigarh on April 10, I knew I lived in a time history books and period films of the future would try to depict. I lived in the midst of a revolution, at a time when the youth the world over are rising up, overthrowing governments, making history.

When I walked towards my polling booth in Sector 11 in Chandigarh on April 10, I knew I lived in a time history books and period films of the future would try to depict. I lived in the midst of a revolution, at a time when the youth the world over are rising up, overthrowing governments, making history.

I am that youth, part of that revolution.

When people speak about elections, they speak about youth disengagement. Disillusionment. Perhaps they haven’t met the new youth of India.

Look at the incredibly talented All India Bakchod mocking the Congress and the BJP on YouTube. Look at the Aam Aadmi Party memes. Look at the thousands, the tens of thousands, who consume, spread those messages.

We are the new youth. We are engaged. And today I would seal my engagement by casting my first vote, ever. It was my duty. My chance to change my nation.

My city of Chandigarh is an interesting place. A Union territory serving as capitals to two states, Punjab and Haryana, it is not your average Indian city.

It has the highest human development and gender development indexes in the country. The third highest per capita income. Ninety-seven per cent of its population is urban, and the literacy rate is high, 86.43 per cent, compared to the national average of 74.04. Two Bollywood actors and an ex-federal minister are contesting the elections, and who comes to power will be a reflection on the sentiments of the educated, urban, high-income segment of the Indian population.

The 800,000 people of Chandigarh are spread across 63 sectors. Each sector is allotted a voting station, with one or more polling booths, depending on the population density.

My own booth was at the Government High School in Sector 11. Before I started out at 11am, my mother had checked on the web site of the Chief Electoral Officer, Chandigarh to see if there was a long queue. There wasn’t.

I entered the school through a small side gate, along with three others voters – an elderly couple and a middle-aged man with a Blackberry glued to his ear. A policeman was at the entrance. Spotting the couple tempting gravity with every step, he signalled to someone inside. A man rushed out with two wheelchairs. I was surprised. I had certainly not expected it to be organised to this level.

I queued up with some 10 people. Sector 11 had been divided into two, with a polling booth for each division. I could see senior citizens given priority and taken up to the head of the line. Within 10 minutes, barely one page into my book, it was my turn.

My identity was verified by four government officials, who matched my face to the photo on my voter’s card. Before I entered the booth, a fifth rechecked my identity and marked my index finger with a semi-permanent black dye. I had waited for that mark for long.

I pulled a grey curtain shut behind me and stared at the machine in front. I had always imagined the voting machine to be like an ATM. It was, only smaller.

There were about 10 names on the machine. To my dismay, they were all in Hindi. While the symbols were in most cases sufficient to let the voter know which button to press, it would have been good to have the name of the party in English as well. My grandfather, for instance, could not read Hindi. He would have been confused.

I pressed the button I wanted to. I heard a ping, the kind you hear when you summon assistance at hotel receptions.

It was done.

When I walked out into the hot sun, I was a democratically engaged Indian. By pressing a small button, I helped determine the course of India, and, to some extent, that of the world. I helped determine whether India will be a Communist nation, or whether it will follow a capitalistic model fuelled by trade and industrialisation. I determined whether equal rights will be granted to the LGBTQ community, whether sectarian policies will rage.

I took a stand on issues that matter to me — to us — today. I exercised my right to take that stand, and I am proud of it.

That is why I want to hold on to that black stain on my finger for as long as I can.

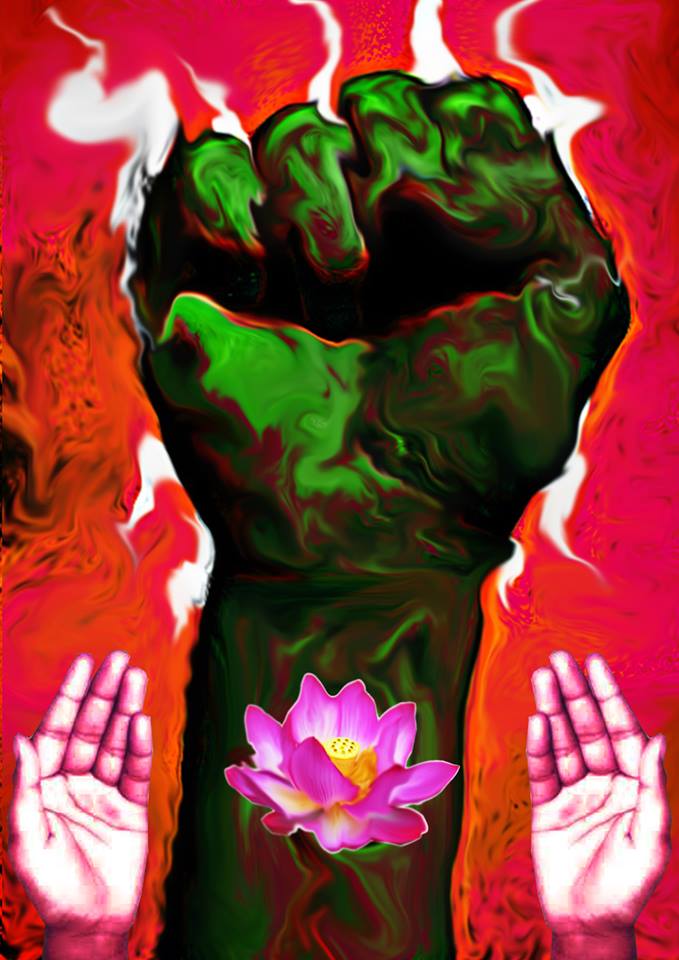

Image: Nabarun

This story was also published on Rediff.com, our media partner.

‘Why are you not speaking up? Why is asking a candidate about their position on gay rights unheard of?’

Seems silly, I know. But only until I tell you I’m gay. Then you see why I’m keeping my identity a mystery. The resigned curve of your mouth stands testament to your tacit approval of my decision to retain anonymity. Do you know what that reinforces? That I’m not recognised most of the time, and that when I am, it’s not in a positive way.

I know that, so I hide. You know that, so you let me stay hidden.

The carpet under Indian society is filled with members of the LGBTQ community, stuffed away like if you leave us swept under long enough, we’ll go away. But here’s the thing. You can pretend we’re not there as much as you want, that doesn’t change the fact that we’re there and we’re getting louder, we’re getting angrier. We’re not going to keep it down much longer. We will break free from these arbitrary prejudices and constraints. We’re not going to stay hidden anymore. The question is, will you still pretend we’re not there? Or will you stand behind us?

We’re voting today. Tens of thousands of people are casting their votes to decide who should be in charge, who will look after their interests best. The poor look for welfare schemes, the tribals look for education and empowerment, women look for safety — and there’s someone out there for everyone. But hi, I’m the LGBTQ Community and you forgot me. No, worse. You see me in the corner, struggling to keep myself afloat, but you have decided I’m not worth looking out for.

Do you have any idea how that feels? Being treated like a second-class citizen? I hope you never do, because it’s awful. Nobody is the ray of hope to offer me a way out of this closet. Nobody has even hinted at the possibility of providing me a safe place when I decide hiding is not for me anymore. Is that fair?

The rant of this member of the LGBTQ Community is against the world. Yes, I’m giving in to the cliché. I hate the world. I am angry, firstly at the political scenario of this country. How can you call yourself a democracy when you’re denying an entire community basic rights? How can you, a nation that has long been hailed a haven for people of all communities – Jews, Buddhists, Muslims, Hindus — possibly be called diverse and welcoming when all you do is spread hate to this community? It’s hypocritical. And it’s wrong. And one day, far into our future, we’ll look back at this, the way we look at the deplorable treatment of untouchables, and we’ll shudder at the cruelty, the ignorance, of mankind.

But more than the politicians, I am angry at the society. You’re the ones who elect these fools. You’re the ones with the power. Most of you reading this have been educated, learnt of Gandhi and math and human rights. Why are you not speaking up? Why is this not the most important thing? Why is asking a candidate about their position on gay rights unheard of? The government is what you made it. So when I blame the government, I’m also blaming you.

I’m trapped. Society won’t accept me, so I’ve resigned myself to live a lie. I walk around in constant denial of who I am to avoid being persecuted — and trust me, the harassment I face is real. It needs to stop. I need you to fight for me, create a situation where I feel safe and supported enough to fight for myself.

We’re in the midst of history, and I want you to be on the right side. I’m not voting because there isn’t a single candidate who represents my needs, my wants, my basic human rights. And that is something we all forgot to talk about. And what does that say about us? The situation is so bad that I, and a countless number of others in the same position, are planning to escape the nation. Yes, escape it.

Is that really the kind of nation you want to live in? The kind people want to escape?

Ignorance is not bliss. This year, read, learn and talk — let homosexuality be one of the most talked about subjects. Once we’re talking about it, misconceptions will be lifted. Help us.

As told to Saba Sodhi in New Delhi. The interviewee requested anonymity, and the interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

The image used above is a painting by the interviewee, titled ‘Dualist’.

This story also appeared on Rediff.com, our media partner.

“ I can see how you will look at me when I say I have not voted. But you don’t understand. You don’t understand I don’t live in the same world you live in ”

- Reba, maid, Uttar Pradesh -‘I have never voted. Maybe this time I will, for the new generation’

My name is Reba. I think I am 37.

The village I was born in, a few hours out of Kolkata, is one of those places nobody knows about. You don’t come to know about it even when you walk through the middle of it. And it’s for that reason that I have no voter card, no ration card, pretty much nothing. So I have never voted.

I have four children. Three daughters and a son. Today was a difficult day. While cutting vegetables at one of the nine houses I work in as a maid, I cut my hand. A nasty gash. I poured water on it and pressed it with a damp cloth until it stopped bleeding. But by the time I reached the third house of the day, the strong phenyl and acid combination I used to mop the floor had infected my wound. I blinked back tears and carried on. After 13 hours of work, with on 15 minutes for lunch, I got home. Instead of collapsing on my bed, I repeated my actions of the day – wash, sweep, clean, dust, cook. This time I was working for my home, my four children, my husband.

Yes, I can see how a lot of you will look at me as soon as I say I have not voted. My daughters — I’ve educated them, one of them is even doing her Bachelor of Arts from Delhi University — look at me the same way. But you don’t understand. You don’t understand that I don’t live in the same world you live in.

You sit in your rooms, debating whether India ought to take a stand against the Naxalites, typing furiously into your laptops about whether or not the price of petrol is inflated. What you don’t understand is that my bicycle and I really don’t care.

I care about feeding my children, I care about helping them escape this torture I’m living through. I care about being able to smile on my deathbed and consider my life determined solely by the quality of life my children live. And nobody actually helps with that. Not one party.

It all sounds very fancy. It all sounds as if they have these grand schemes to help us, but that’s all they are: schemes. I don’t vote because even though I now have an Aadhar Card. Even though my daughters are educated and smart and talk of how important it is to vote, I’m jaded. I’ve been sidelined, ignored, forgotten by the entire political scene. So much so that I don’t ever remember being part of it.

My daughters say I cannot complain about my politicians if I don’t vote. That I can’t talk about a broken system if I don’t do anything to change it. But to me, voting for the politicians here is as useful as voting in Bangladesh – inconsequential. They make big promises, these big men, but I’m no longer affected.

Perhaps my attitude is defeatist, but you tell me this: what child is born with that attitude? We’re all born clean slates. Take something from that. Look at why I am this way. It’s because of a lifetime of disappointment.

The new generation is full of hope. The new generation is full of fire. And maybe this time I will vote. Maybe I will, not so my life gets better, I have given up all hope for that ever happening. But for the new generation. I pray the politicians won’t turn them into fragile, cynical things. I don’t know whom, I don’t know how, but I’m praying for somebody, and this time maybe I’ll do it with a ballot in my hand.

As told to Saba Sodhi in Noida, Uttar Pradesh. Reba, who requested partial anonymity, spoke in Hindi and Bengali. This interview has been translated, condensed, and edited for clarity.

Photo credit: Vishal Darse