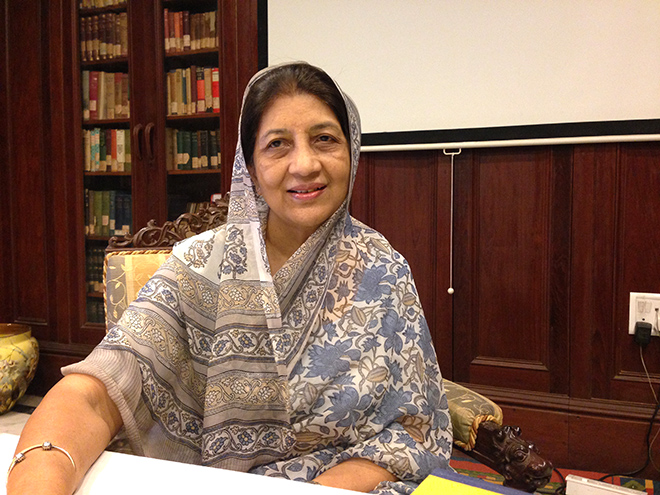

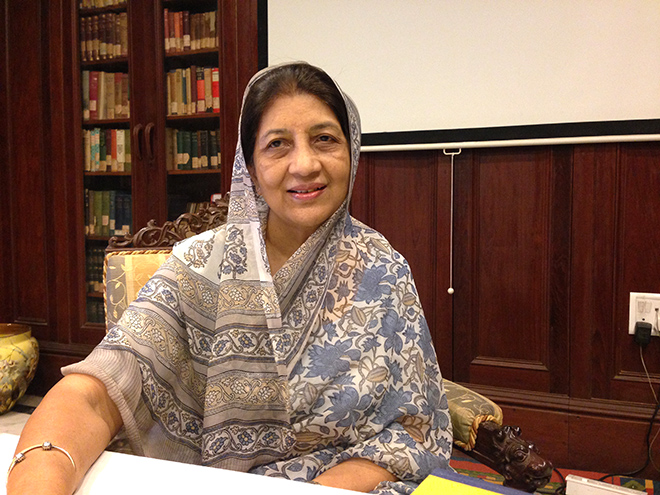

Turning off a busy main road in Baroda, the scene suddenly becomes tranquil, away from the hustle and bustle of city life. Ahead is the majestic 19th century Laxmi Vilas Palace, an Indo-Saracenic Revival building surrounded by acres of flat grass complete with golf course, monkeys and peacocks.

This is the home of Shubhanginiraje Gaekwad, the rajmata (queen mother) of Baroda. After a long hiatus, she has made a political comeback as one of those who proposed Gujarat chief minister Narendra Modi’s candidature for the Lok Sabha constituency of Vadodara.

We wait in a large room adorned with paintings of royals past, piles of books and a chandelier fitted with energy-saving bulbs. After a while we are invited into a bookcase-lined room to meet the rajmata, who sits at the head of a long table, her iPhone in front of her. On the wall is an old map of what was once the kingdom of Baroda, one of the wealthiest princely states, whose Maratha monarchs were among just five Indian rulers accorded a 21-gun salute by the British Raj.

Shubhanginiraje’s husband, the late maharaja Ranjitsinh Pratapsinh Gaekwad, was known for his passion for the arts and cricket and for his paintings. He was also elected twice (1980, 1984) to the Lower House of Parliament on a Congress ticket. The rajmata herself contested the Lok Sabha elections twice, once as an independent candidate in 1996 in Baroda and again as a Bharatiya Janata Party candidate in 2004 from next-door Kheda but without success. She speaks to Patrick Ward on Modi, Gujarat, communalism and Rahul Gandhi.

Does your nomination of Narendra Modi mark another attempt to enter the political fray? If so, why now?

I don’t know. When Mr Modi decided he would like Baroda to be his constituency, I was one of the persons he asked and I agreed because I am glad we are getting someone like him to represent us.

I am supporting the BJP for these elections. The people of Baroda don’t forget us. They still remember us.

Why did he ask you and why did you agree?

I can’t say why he asked me. Probably he wanted my family’s support. He wanted people from all walks of life to support him and I am not his only proposer. Also, I think he wanted to pay respect to our family and the work done by them. You talk to people in town and they still remember the good administration they received during the reign of the Gaekwads. This was during British India, of course.

Modi comes from a small place called Vadnagar, which was part of the old Baroda state. Baroda state was quite extensive, disjointed and vast. It wasn’t easy to administer the entire area, but it was still well done. At that time, only Baroda achieved cent per cent primary education for every child in the state. So, I guess, he wanted to emphasise that because he said, ‘I am a product of that. I received education in a small village because I was part of Baroda state.’

I appreciate Modi because of the credit he gave. Most often, people want credit for themselves. So I appreciate it when someone like him in his position thought of giving due credit. No one would have thought about it if he didn’t mention it. No one would have missed it. This is something from over 100 years ago. Did you know that there was a book published in the times of Maharaja Sayajirao about learning the ropes of good administration? Modi actually got it translated into Gujarati and English and gives it to all his administrative staff. “I give this book whenever new officers come so they can learn something from it, even how to deal with each other, but they would learn the good administration that prevailed in Baroda state,” he said on the day he signed his nomination papers. In a six-minute speech to talk about this for 3-4 minutes is quite telling.

There’s talk he might win both Vadodara and Varanasi and will have to choose between them. If he gives up the Vadodara seat, would you or your son Samarjitsinh be interested in contesting the by-election?

That is for the party to decide. I have no idea just now. I might consider it if they think it is the right thing to do.

Most often, when royalty enters the political fray in India, they do very well. Why were you unsuccessful in those initial rounds?

Once I stood as an independent, so that was a little tricky because there are two big parties against you. Voters were also fewer in number and I remember the race was neck to neck. I got exactly one-third votes. The Congress candidate, who won that year, only won by a margin of 17 votes. It was all last minute and not much preparation had been done. There was also a lot of confusion.

Most people always associated my husband with the Congress. That year, the Congress fielded a candidate with the same last name — Gaekwad. This got people confused in the rural areas. Today, things are a lot better; voters are smarter, more educated.

The next time I stood as a BJP candidate, but I didn’t stand from Baroda, unfortunately. I stood from Kheda, a stronghold of the Congress. The sitting MP was there for two terms, and I told the party I was not at all keen, because I knew I was stepping into a disaster. At that time, (Atal Bihari) Vajpayeeji personally requested me and I got pressured. I said, “I think I’m going to lose, but because you telling me to stand, I will do so.” So I went and followed my party’s orders.

Are you politically active? Do you attend party meetings?

No, I haven’t been very active since. When I stood independently, my husband had left the Congress. Before that he was not active and was totally disillusioned with the party. But having been in the party, he didn’t want to go and join another party. His temperament was not to jump from one party to the other. So he left the party. Otherwise he wouldn’t have canvassed for me.

He did more campaigning for the BJP later. He even campaigned for the BJP candidate in Baroda.

After (former prime minister) Rajiv Gandhi was assassinated, which was tragic, things changed. I think when (Congress president) Sonia Gandhi joined the party, he became totally disillusioned. Your worth in the party was just how much you could please some people. He said, “I can’t do those things.”

Why do you think the BJP is a good option?

They are a good option. What other choice do we have? Surely we can’t have (Congress vice-president) Rahul Gandhi? What are his credentials? He hasn’t proved himself by being a minister in a Cabinet, he hasn’t done a day’s job in his life. He hasn’t proved himself in any task. I feel, as a young man, one at least ought to go out and earn one’s living. All our young boys and girls are working so hard. But look at him. Here he is, a young fellow, accept him as prime minister. Why? What has he done?

Our country is so very diverse and complicated. It is not the same, every part is different. You need someone to have thought about these things deeply. Someone who is mature, and it is not just his age that’s an issue. Some people do their best at a young age. But he has done nothing.

Can Modi reproduce what he has done in Gujarat across the country?

He can try. At least you have a man who has sincerity of purpose and does his best. He has been working hard for the past 12 years in Gujarat. At least he’ll try his best. He is from the grassroots, he knows what is life, he has seen that. In all areas of Baroda constituency, he will definitely do very well. I am sure he is going to win, there is no doubt about that. I am sure he has already gauged that, which is why he has come here to a seat he was sure to win. He knew he was not going to devote much time to Baroda constituency, or any constituency in Gujarat for that matter. So, obviously, he was looking for a safe seat. He is concentrating on all parts of the country now, how much can he be here?

He is a good choice. They need someone who has drive, who has charisma, who can attract people with his talking. As a prime minister, Manmohan Singh is educated, probably much more educated than Modi, but he could not make a good prime minister, people never related to him. And then, of course, there were these two power centres, which was so pathetic.

It’s disgraceful, the office of our prime minister has been degraded thanks to the Congress president. Once a person is on that chair, we have to respect that chair.

What should Modi’s priority be should be become prime minister?

It should be to bring efficiency to the administration because the common man suffers because people who should be doing their job, don’t. Especially in government offices, applications should be dealt with in a swifter manner. People should be tended to, but people don’t do their job.

Also, great reforms need to be introduced in our judicial system. People wait for years to seek justice, but even after 40, 50 years, they don’t get it.

Lastly, a lot of attention has to be paid to infrastructure.

What about communalism?

Some people keep talking about it because they don’t want the people to forget about it. People just want to let it be, forget it and carry on with their lives. Everybody wants to move on. The youth is not bothered. They want jobs, they want to earn a living, they want infrastructure.

Communalism is always raised as an issue by politicians. They want to make an issue where there is no issue. I don’t deny that it is an issue, but it is prevalent all over the country. It is not like Gujarat has more of it than any other part of the country.

No doubt, what happened in Gujarat was sad, but the Congress government at the Centre has always harped on this as this is easy for them. They want to keep it fresh in people’s minds so that people outside the state believe the situation is worse that what it is.

We have had communal riots in Gujarat for many years. Even when my husband was in Parliament we had problems, but it was instigated by some local goons. When there is a Hindu festival, there is a problem and vice-versa. These situations are just manipulated most of the time.

So you think the Congress raising the issue can create divisions?

Exactly. What was the need for (Congress president) Sonia Gandhi to call the imam of Delhi to her office and tell him, “Please tell all the Muslims to vote for the Congress”? You can’t do that. You may tell him in private, that’s all right, but you can’t call him and tell him and make an official statement on television. This means you are already dividing the country and its people.

Why are you dividing them on the basis of religion? Let anyone vote for the Congress, let anyone vote for the BJP.

What about the hate speech made recently by Vishwa Hindu Parishad leader Pravin Togadia?

There are a few people like that, talking rubbish. But there are people like that on all sides. You can’t go on controlling the way people talk and elections only make people fiercer in their speeches. Politicians talk like that to divide the people, but as a party, the BJP has not tried to do that. Modi has tried to bring people together. The Congress, on the other hand, has only tried to appease the minorities, especially the Muslims, which I don’t agree with. Why appease them? Why aren’t there the same rules for everybody? Why can’t they follow the law of the land? This only makes other people irritated about the situation, causing an anti-Muslim vibe. This is the policy of the government, which benefits a few people.

This interview was also published on Rediff.com, our media partner.

Photos: Vaiyhaysi P Daniel/Rediff.com