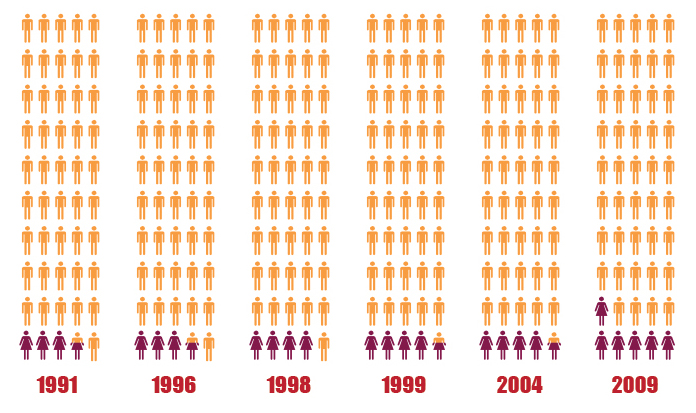

While 66.38 per cent — 551 million — exercised their democratic right across the 190,000 polling booths across India, and 32 of the 35 Indian states and Union Territories saw a higher turnout than in 2009, 33.62 per cent Indians did not vote.

That is 264 million voters — six times the population of UK — who did not get inked.

The top performers in the elections were the smaller states: Nagaland (88.6 per cent turnout), Lakshadweep (86.8 per cent) and Tripura (84.3 per cent). And in Goa, Punjab, Chandigarh and 13 more states and Union Territories, the female turnout was higher than that of males.

As for the most populous states, many performed poorly. In Bihar, 43.5 per cent did not vote. And from among the 200 million voters of Uttar Pradesh, 41.4 per cent did not — or could not — vote.

Project India reporters spoke to voters in several constituencies to get a sense of why they did not cast their votes — and what they would like in future elections. Here’re some voices:

Somipoem Keshing, Manipur: ‘It’s all a big scam’

Indian election is a big scam. Most people are simple-minded and they are easily influenced by politicians hunting for votes. Democracy is a beautiful system, but it is easily twisted by political strategy. Democracy says a government for the people. Unfortunately, that is not what happens. The government is monopolised by the powerful candidates. The rich candidate comes to power again and again. The poor remain poor – again and again. There is a deep contradiction between the real politician and the politician who appears on your TV screen. They are not the same. It’s all a big scam.

Komal Sheth, Pune: ‘An online voting system is the answer’

I moved from Kolkata to Pune two years ago. My voter ID was already made in Kolkata and there was no provision for me to transfer the voting constituency to Pune. My hectic college and work schedules didn’t let me travel to vote in my constituency. I had prepared to vote and created my photo ID, but I didn’t get the chance. I feel bad and disappointed. It would have been more satisfactory if there is better provision for people who move due to work or education. An online voting system is definitely an answer, but we still need to figure out how it would work.

I moved from Kolkata to Pune two years ago. My voter ID was already made in Kolkata and there was no provision for me to transfer the voting constituency to Pune. My hectic college and work schedules didn’t let me travel to vote in my constituency. I had prepared to vote and created my photo ID, but I didn’t get the chance. I feel bad and disappointed. It would have been more satisfactory if there is better provision for people who move due to work or education. An online voting system is definitely an answer, but we still need to figure out how it would work.

Hari Gaurav, Chennai: ‘My vote is not going to change anything’

I have completed my BE from a city college. I didn’t vote. I opted not to vote because none of the parties have promised free education for financially poor students. None of the parties have promised to develop the quality of education in India. I prefer to be a non-voter than vote. My vote is not going to change anything.

Eric Kapadia, Mumbai: ‘It didn’t make the slightest difference to my life’

Having lived in Canada for the past two years now, this was the first time I was away during elections. Although I couldn’t come home to vote, it didn’t make the slightest difference to my life. All these politicians only focus on places where they know they will get a large number of votes. Maybe that’s why nobody votes in South Bombay – not because we’re snobs, but because if they don’t seem to care about us, then why should we care about them? But the day a leader rises and has the courage to talk about issues that are swept under the rug in India, that’s a day I would look forward to voting.

Arsilan Lone, Srinagar: ‘I will not betray the martyrs’

I will never vote for any pro-Indian politician in Kashmir. They are nothing but stooges of New Delhi and just strengthening the brutal occupation by India. I am part of the future of Kashmir and I will not start my life by kissing the hands that are red with the blood of our brothers and sisters. I will not betray the martyrs. It doesn’t matter whether pro-freedom leaders give election boycott call or not, I know my moral responsibility very well. I was born in an occupied nation but my mind and heart have never accepted that.

I will never vote for any pro-Indian politician in Kashmir. They are nothing but stooges of New Delhi and just strengthening the brutal occupation by India. I am part of the future of Kashmir and I will not start my life by kissing the hands that are red with the blood of our brothers and sisters. I will not betray the martyrs. It doesn’t matter whether pro-freedom leaders give election boycott call or not, I know my moral responsibility very well. I was born in an occupied nation but my mind and heart have never accepted that.

Rahul Shah, Mumbai: ‘Why aren’t the roads fixed?’

If I was interested in politics, I would have voted. Nobody within the political sphere seems to care much about the political good. If I’m not wrong, this is one of the constituencies that gets the largest share of funds. So why aren’t the roads fixed? What is happening to the filth everywhere? Nothing.So what difference would it have made if I voted? I have my voter’s ID and the polling booth was just opposite my house. Still, I chose to go for a holiday.

If I was interested in politics, I would have voted. Nobody within the political sphere seems to care much about the political good. If I’m not wrong, this is one of the constituencies that gets the largest share of funds. So why aren’t the roads fixed? What is happening to the filth everywhere? Nothing.So what difference would it have made if I voted? I have my voter’s ID and the polling booth was just opposite my house. Still, I chose to go for a holiday.

Rishabh Gupta, New Delhi: ‘If only the EC had been more efficient’

I would have voted for first time in this election if the Election Commission had eased out the ways to register for the voter ID card. I had registered myself with all my details on Election Commission’s website but nobody came to verify the details at my home. When I enquired from officials who distribute voter ID cards they told me to visit the regional office but I was not able to visit due to my college. I am very sad that I was not able to vote in this transformative election. I wish I could have voted. If only the election commission had been more efficient.

Nandini (not her real name), Mumbai: ‘I didn’t vote because I don’t want to give them power’

Being an 80-year- old woman, I have been a part of Indian history. I was there when the first general elections took place. I’m not proud of the fact that I didn’t vote, but it doesn’t bother me. Every day there are the same news: One politician says something to another, so the party gets angry. Everyone starts shouting, not allowing other people to speak. Tell me, how am I supposed to take these people seriously? I didn’t vote because I don’t want to give them power. I think the entire concept of elections is beautiful. One citizen giving power to another. But as soon as the power is given, some people then do nothing. Instead, they take my money and build themselves big fancy homes. And this merry-go-round has been happening for years. So if I vote, I will help turn the merry-go-round, reinforcing the cycle. Now that’s something that would bother me.

With inputs from: Zulkarnain Banday, Rachitaa Gupta, Manolakshmi Pandiarajan, Jehan Lalkaka, Anshul Gupta, and Deepa Venkatesan.

Photo: rajkumar1220, Flickr CC