Author: Patrick Ward

In the other Varanasi, there is no need for May 16. Modi has ‘already won’

As the long and punishing polling for the 16th Lok Sabha elections ended with the grand finale of Varanasi in Uttar Pradesh, where BJP prime ministerial candidate Narendra Modi is fighting a historic battle, Rediff.com‘s Vaihayasi P Daniel and Project India‘s Patrick Ward joined hands to offer a view of Baroda, Modi’s second constituency. Here, in this safe seat from Gujarat, his victory is seen as a done deal — despite scars of the 2002 riots among the minority Muslim population.

The first thing that struck us about Baroda was the quiet. Sure, the city was plastered with election posters. Posters that brandished a finger, admonishing you to vote for Narendra Modi. Posters and posters and posters. They were on every wall, underpass, and bridge, crowding out the billboards of Congress leader Rahul Gandhi, submerging him in a cacophony of silent Modi-figures with tough Modi-glares glinting through steely Modi-glasses.

But one thing was missing. There was no noise.

A few days before the polling day when we visited Baroda, Modi’s ‘home’ constituency in Gujarat, there was no real election buzz. That intangible election energy, which hangs in the air when you enter every Indian town about to vote, that was absent.

At the Bharatiya Janata Party’s central office in Sayajiganj, just before sundown two days before campaigning was to end, a solitary Modi-vehicle, with a nearly life-size cutout of Modi’s head fronting its bonnet, was parked outside. Devotional music spilled robustly out of its speakers into the lobby.

Bharat Dangar, the BJP president for Baroda City, sat at a broad desk, a lotus pinned to his chest. There were saffron rubber bands on his desk, and he was to later say they handed out saffron hairbands as well (saffron being the BJP’s official colour).

The faces of Modi and other BJP politicians formed a panorama behind Dangar, affording him some additional heads, like a Hindu deity. He had all the constituency facts at his fingertips and could reel out pretty much any statistics you asked for. He brimmed with confidence and self-satisfaction. As far as Dangar was concerned, the constituency was already won. There was no need for May 16. Modi was well on his way to 7, Race Course Road.

“Everyone knows Modiji will win with a big margin. We want to create a history over here,” Dangar said. “This is the first chance a Gujarati, as a Barodian, will vote for the PM and not [just] for the MP. We have 543 constituencies in India. Among the 543 only Varanasi and Baroda will vote for the PM. We are the lucky ones… After the fifth or sixth phase it was clear, very clear that the BJP will come in the power, NDA [the National Democratic Alliance] will come in the power. And Narendra Modi will become the prime minister of the India.”

Modi had stopped by in Baroda for a large rally on April 24, for just four hours, from 8 am to 12 noon. That was all Baroda saw of Modi. Such was the confidence the BJP claimed to have in Baroda that Dangar said he was certain of a significant win.

“Everyone here is Narendra Modi.” Dangar said. “He himself said that at our public meeting. Everyone here is a Narendra Modi. Why should I take stress because everyone here is a Narendra Modi? Not by birth. But by their work.”

By that logic, Baroda, a city if 1.637 million, is a city of 1.637 million Modis. And every single one of those 1.637 million Modis would vote for Modi. That sounds like good electioneering, and you cannot but admit that Modi and his campaign advisors know how to play the crowd.

Dangar was quick to agree there was not much electoral buzz in Baroda — not too many rallies, not too “much voices or noise”. What was not evident to the casual observer, he pointed out, was the extensive door-to-door and meeting-based campaigning the BJP was undertaking — particularly in rural areas, which account for some 500,000 voters.

Most of their work was volunteer-driven, Dangar said. The BJP has 10,000 registered workers in Baroda and many more volunteers, and the main strategy had been to pay special attention to the electoral list, which runs to 25,000 pages, with between 45 and 48 voter names – roughly 10-12 families – per page. For each page, one resident had been chosen ‘Page President’, Dangar said, and it was his/her job to mobilise the others listed on the page to vote for Modi.

So how many Page Presidents did he have in all?

“Twenty-five thousand!” Dangar said, with evident glee.

If there was a spark of electioneering activity visible a few days before polling, it was at the Congress candidate’s rallies. Taking on Modi in a constituency where it is predicted he will triumph with a margin never seen before is all about guts and no glory. And Madhusudan Mistry came across exactly as that kind of feisty fighter as he addressed shockingly tiny rallies — a hyperactive stage actor without an audience. He matched the smug BJP hyperbole word for word.

It must be a very tough fight for him. Why did he take it up?

“Why not?” said Mistry, who sported a mop of long white hair. “When Enoch Powell [the British politician notorious for his controversial Rivers of Blood speech against immigration] contested in Britain, somebody took him on as well. He lost. But they fought.”

So it is because somebody has to stop Modi?

“Yes. Someone has to expose him,” Mistry said. “What sort of person he is. What his development model is. I would say it is purely a facade. He talks about development. In the back of his mind is a very clear-cut vertical divide that he wants to inject between Hindus and Muslims.

“If he ever gets elected and if he ever becomes the prime minister, the first thing he will do is declare a war with Pakistan, to get himself established as a hero in the Indian psyche. His rhetoric against the Muslims and the minorities will continue.”

What is the best change Modi has brought to the state? Mistry shrugged.

“Tell me, in which sector is Gujarat leading the country?” he challenged. “Tell me one. Manufacturing, services, industry, agriculture, health, education? Which sector? IT? Name one?”

Mistry is a mean speaker, and not without talent. He continuously attempted to fire up the audience at the Vagodia area in Savli. But still it was at best a dull show.

The audience sat collapsed in white plastic chairs, listening, but largely unresponsive. The rally, which took place on the side of a main road, caused the traffic to pause only occasionally. Now and then someone would stop by on their motor scooter to listen for a few minutes, before losing interest and carrying on. Once in a while passers-by yelled a jibe: “We have had enough of Congress.”

A group of women at the front of the rally pushed forward and surrounded us when we said we were journalists. They begged us to visit their homes and see their plight.

“Why would I not vote for the Congress? They look out for the poor! Modi cannot even look after his wife,” said Neelu, a factory worker, referring to the recent controversy about Modi abandoning his wife for politics.

Geeta Rajput, from Vaghodia, who washes dishes for a living, lives in one of the government-built housing projects that have slowly started replacing the city’s original slums. She was upset her home leaked water, and she could get no city official to solve the problem.

It was about 9 pm. From Vagodia, Mistry headed to a rally at Raopura, an area where he believed he had good support. Raopura voted in a BJP legislator in the last assembly election; it is mixed area of Gujaratis, Uttar Pradesh migrants, Baroda Maharashtrians, and Dalits.

The audience in Raopura was larger, more attentive to Mistry – but still not enthused. If one were to try to gauge the audience reaction it would seem they were here to judge if Mistry might make a better alternative.

Chaya Rajput, 33, a housewife who sat listening to Mistry at the back of the rally said, “At my in-law’s place all of us like Modi. We like the work he has done very much. I have no fear [that he will bring divisive politics]. Ever since I have grown up and matured I have been seeing his government.”

Rajput said her family liked what Modi had done in the state, especially with respect to education, roads, water, electricity. For her the deciding factor was contrast she saw between Maharashtra and Gujarat, when she went to visit her sister in Shahada, Maharashtra, across the border from Gujarat.

“There is no light there,” Rajput said. “The roads are so dark. But when you reach the Gujarat border, it is all light.”

Mistry said he worked hard trying to attract disaffected voters to his cause. “You just have to go on talking to the people. Be with them, explain to them, mobilise them.”

What does he like least about Modi?

Mistry laughed as he mulled over that question. “I don’t know!” he finally said. “I have never answered this sort of question before…”

Then he added, “He never tell you the truth. He is a five-step liar. He will tell one lie to a subordinate. And then he will convey it to one person. Then he will convey it to the fourth person. The fifth person will go out and tell. And from where it originates nobody knows.”

The poor, be they hawkers or workers, according to Mistry, are still drawn to the Congress because the Modi Dream is not one they feel they can realise.

“It depends on what sort of person you talk and interview with. If they are people who are doing a little well economically they will naturally be siding with him. This has been the history of Gujarat. Wherever there was a good economic status we always supported the right wing people.”

“We never supported the African National Congress in South Africa or a Labour Party in Britain or Labour in Australia. We are always with the Tories and in the US as well. This has been the psyche in the state with whoever is outside. Mainly those who have money will always be siding BJP.”

Why did Modi choose Baroda — with 11,539,68 male voters, 10,717,95 female voters and 34 other voters, as per the latest Gujarat census figures — as his constituency?

Professor J S Bandukwala, a human rights activist who narrowly escaped death when rioters burnt down his in 2002, said: “He chose Baroda because this is the most BJP-oriented constituency in Gujarat.”

Because of the RSS impact from its headquarters in central Maharashtra?

“Not only the RSS impact. The impact of people abroad. This is the Patel-Patidar area and every family has someone abroad. There is a very large population in America and they are very fanatical, most of the Patels. This is their centre. They are all settled in New Jersey and other areas. This is the one constituency he doesn’t have to bother about.”

If Modi wins both Varanasi and Baroda, will he step down from the latter constituency? We asked Dangar that, but he refused to answer.

“Our aim is to make a historical victory,” he said.

Modi will most likely triumph in Baroda, but will the industrious 25,000 Page Pramukhs succeed in bringing some of the city’s approximately 300,000 Muslims to vote saffron? Javed, a taxi driver who took us around, thought so.

“The riots took place in 2002. Things have changed since then,” he said. “Modi has found a place in our hearts. He has brought progress. He has provided jobs.”

Bandukwala, who has a daughter and son settled in the US, and a Hindu Gujarati son-in-law, had this to say of Modi:

“Many Muslims have become resigned to him. They will just accept him for whatever he is. Which I can understand. Small people in public cannot say anything, for fear that there may be a reaction.”

He continued, “Muslims are in a real trap just now. There is an intense fear also. If you go below the surface you will find an uneasiness. We don’t know what is going to happen. We don’t know. That fear is very deep. Society is completely communalised and divided. I don’t know where we will be headed.”

Baroda has a scarred history. Though some of the worst incidents of the 2002 Gujarat riots that saw about 1,500 casualties took place 111 km away in Ahmedabad, Baroda too witnessed deaths – some 36 people were killed in the ensuing violence in the city. Its proximity to Godhra also meant that scores of Muslims fled to Baroda. There was more Hindu-Muslim violence in 2006. But is it possible that BJP might have gained some Muslim voters who are willing to put 2002 behind them?

Mistry said, “In the constituency I was representing, I don’t think they have put it behind.”

As we travelled through rural Gujarat the next day, we quizzed Muslim voters about their preference. The much-touted Gujarat model of Narendra Modi seemed to not have percolated these areas; and despite what Dangar claimed, many Muslims among the 1.637 million voters of Baroda were not Modis, but anti-Modis.

Bandukwala’s words seemed to acquire a ring of truth as we left our last interviewee. “Muslims voting for Modi would be very low,” the professor had said. “Those who have joined with Modi have been ostracised in the community.”

A version of this story was first published on Rediff.com, our media partner.

Photographs: Patrick Ward, Vaihayasi P Daniel/Rediff.com

The recipe for democratic engagement

At the end of the day on which Mumbai got its collective finger inked, I was filming a selfie outside the gates of a school near the vegetable market in Byculla in Mumbai South. It was less narcissistic than it sounds – I was finishing off a day of intense live blogging.

It was going pretty smoothly, until I noticed the watchful glare of a police officer, who ambled over, and stood in front of me, his arms folded. I rushed through the remaining sentences, trying not to lapse into awkward gibberish as I did so, and put my phone in my pocket.

“What are you doing?” asked the young officer, gesturing at my pocket.

“I’m just…” I hesitated, “…filming.” I quickly added, “I’m a journalist covering the elections.” The policeman’s brow was still furrowed as he hit me with a follow-up.

“Are you here on a visa?” he asked. “Which one?”

We had a little back and forth like this until I realised it was inquisitiveness rather than inquisition. It turned out that he had been working nearly non-stop for 48 hours.

“So what do you think of democracy here?” he asked. I told him how much I was struck by the level of engagement, especially coming from Britain where voter turnout is generally far lower.

“People here are very proud,” he said. “Everybody votes. Why don’t they in Britain?”

I shrugged. “Maybe it’s because people think all the parties are the same?” I suggested. “There’s not that much difference between them.” My new friend thought for while, then came up with the answer.

“It’s probably because we have a real democracy and you have the Queen,” he said, pointedly. “We can choose for ourselves.”

This story was also published on WoNoBo.com, our media partner.

NGOs challenge the mystery of disappearing voters in Mumbai

Two NGOs have filed a petition with the Bombay High Court to challenge the deletion of 200,000 names from the electoral list in Mumbai.

Some 6,500 people who say they had their names “illegally” removed from the list of electors came forward to support the petition, which was started by the Action for Good Governance and Networking in India and Birthright.

Mumbai’s election day on April 24 saw many voters unexpectedly being turned away from polling stations, despite having been able to vote in the previous general election as well as the 2011 civic polls.

The Election Commission of India has apologised, but the public interest litigation filed by the NGOs calls for a special ballot to be held before May 16 to correct the error.

The PIL suggests either dereliction of duty or political conspiracy as the cause of the names being deleted. It has called for the formation of a special investigations team to look into whether the names were deleted in line with correct procedure.

The PIL has been scheduled for a hearing on May 6, following a decision to do so by a bench headed by the Chief Justice of Bombay High Court, Mohit Shah.

This is the second major controversy regarding the removal of names from electoral lists in this general election. A petition calling for an investigation into the removal of 100,000 names from lists in Pune was filed on April 21.

Photo: Goutam Roy/Al Jazeera English on Flickr cc

This story was also published on WoNoBo.com, our media partner.

The journo who jumped to cover India

It started when I got off the plane and was taken aside by the airport security. Why did I have a tripod but no camera? (It was for an iPhone, because that’s how we roll these days). Why did I have a book about journalism? Where was my gold? And diamonds? And gold diamond encrusted watch? (Actual questions, slightly paraphrased). But my journalistic parachute was yet to be snagged on the tree of unfamiliar bureaucracy and I was let through, phone accessories and all, albeit a little later than anticipated.

Everything was new to me — the climate, the process of hiring a taxi, the language. But I had to get my feet on the ground quickly if I was going to file stories the next day.

This was my experience after landing in the unfamiliar territory of Mumbai to cover the elections as a parachute journalist. Who better to cover The Biggest Election in History than someone who has never seen the place before? As part of Project India, an initiative involving journalists across India and the UK, I am here to give a certain perspective on the month-long general election that is currently underway.

As a first timer, I wasn’t entirely sure what to expect from Mumbai — a city I imagine the un-imaginative but largely correct travel writer would describe as “throbbing”. Sure enough, the damp, smoky night air, the organised chaos of the traffic, and the swarms of people at every turn were a sharp change from the passive-aggression that prevails on the British road networks, and the sleepy evening pavements of Bournemouth featuring only the occasional pub-goer desperately trying to remember their home address.

Parachute journalism is the practise of a journalist with little to no experience of a region being dropped right in there — trying to bring “foreign” stories to a “national” audience. They lack the understanding of the long-term foreign correspondent, and generally don’t stay long enough to develop it fully.

Why parachute? There are heaps of talented (and English speaking) journalists based in India who could tell my stories with far greater depth and understanding than I can. Do we need another European coming from the former colonial power to explaining things?

The trouble with parachute journalism is that’s just what happens an awful lot of the time. Think about the coverage of looting mobs after the 2010 Haiti earthquake, or the forever violent Africans (specific country unnecessary to mention) or the homogenous mass of religious zealots in the Middle East. I can almost hear myself report: “One thing’s for certain, no one can see a way out of this bloodshed and if they could, would they want it? Patrick Ward for Sky News in the Global South.”

There’s also the danger of parachutists developing a pack mentality whereby stories become regurgitated across media. Stories shared by reporters from different agencies and networks over a beer or two in the local journo hangout need to be followed up by all of them, partly because of the ever-present fear that their editor’s number will show up on their mobile phone and they will be yelled at for missing the story.

In Haiti, for example, where starving people were scavenging for food, news reached head offices in London, New York and elsewhere that violent Haitians were coming to blows as their somehow innate savagery came out. If other networks were saying it, it must be real, went the feeling — so journalists had to go out and find that story lest they were left behind. In truth, there was very little violence. And many of the sources used were not ordinary earthquake victims, but US Army spokespeople – leading to all sorts of nonsense about Haitians begging the West to intervene to keep the peace.

Parachute journalists are increasingly relied upon these days because the number of long-stay foreign journalists have declined. This is largely due to cost-cutting and a cynical view spun out by advertising executives and TV network managers that people aren’t interested in foreign news reporting any more. I would tend to argue that it has more to do with the quality of foreign reporting, and its abstract format of stories of flood, famine and flash grenades which appear and vanish from TV screens and news publications without temporal, geographical or political context.

Ted Koppel, a former anchor on the US network ABC, put it well in 2006 when he said, “The approach now is, ‘Well, don’t worry about it. When something happens, we can take a jet and we can access satellites and we’ll have it for you in 24 hours.’ …Have what? You’ll have the after-effects. You’ll have the result of what you should have been telling America about for the last six months. You’ll have the crisis after it breaks.”

But. There can be a merit to parachuting. When my plane landed, seemingly scraping the roofs of one of the largest slums in the world, I perhaps noticed something that would be missed by my fellow nationals at home and maybe taken for granted by the excellent commentators here in Mumbai. It’s the feeling of flying into a country that boasts of its blossoming (if stalling) economy and seeing people without clean water, decent sanitation or functioning electricity. The Indian economic miracle that we read about in the FT or see on BBC News has another side.

It’s more than this too. This isn’t the story of helpless Indians who can’t manage their own affairs. Nearly everyone I’ve spoken to here has an opinion on the election — and an informed opinion at that. Turnout could be as high as 70%. Even speaking to street beggars, they know what they want from the government. Most people want change in India, but everyone has their own view on how that change can come about.

Some people are voting for the right-wing Bharatiya Janata Party’s Narendra Modi because he boosted the economy in Gujarat and would provide a break from years of Congress corruption. Others have a different take, and say Modi’s policies would punish the poor and be a huge blow against secularism. They might want to stick with Congress who, in states such as Maharashtra, have increased economic growth far more than Gujarat, although many would say they haven’t seen the fruits of this. Others disagree still, and want to give the new kids on the block a chance in the anti-corruption Aam Admi (Common Man) Party… but they quit government in Delhi after just 49 days, so can they be trusted?

There are around 1,000 regional parties too, and complex deals struck between them lead to fluctuating coalitions. In Maharashtra, for example, the BJP is working with Shiv Sena, a far-right Hindu nationalist group that wants preferential treatment for Marathis over North Indians, Muslims and others. Election posters around Mumbai for the group essentially proclaim, “Vote Shiv Sena, get Modi”. (Imagine the Lib Dems doing that for David Cameron in the UK.)

Sometimes parachuting in gives you a comparative take on events that you can relate to people in the country from which you came. But it has to be in that context. Read the Indian media. Watch Indian TV news. Follow reports by Western journalists who do obsessively follow the Indian political scene.

I didn’t grow up in a slum and I don’t breathe in the ever-present smoke that marks both industrialisation and lung disease, but I can notice it’s different to what I’m used to. Similarly, I have never felt the fear that a new government might herald the return of inter-ethnic rioting, but through talking to ordinary people I can relay the fears that people have about these things to an audience back home who might never have realised it.

The most important thing a parachutist can do is tell the story of ordinary people in their own words. Rather than rely on coverage by competing Western news sources coupled with government statements and party press releases, the task is to speak to the men and women in the street who want the world to know their concerns, opinions and daily reality.

Parachutists should augment the amazing reportage readily available from people in those countries, not give a 360-degree view of how their society operates that they can then pass off as the only information you will ever need to know. Better still, they should relate it in a way that connects to power “back home” — where is Western investment going? What role do World Bank loans play in this? Whose hand has David Cameron been shaking?

Journalism is facing huge difficulties, thanks to cost-cutting and huge pressures from government to report The Right Line. Parachutists are filling in the gaps vacated by foreign bureaux, and in today’s 24/7 news environment, the quantity of reports demanded of them are ever increasing, and the time to the next big story, wherever else in the world that might be, is decreasing. But we should recognise what we are doing and understand how it influences public understanding. And, most importantly, we should understand our limits.

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

This story was also published on Rediff.com, our media partner.

In the run-up to the elections, Dharavi spots rare birds: politicians

With about a million people, Dharavi was a key constituency for those wanting to get elected to the Lok Sabha this year. It’s also economically important, with an annual turnover of Rs 30 billion (and that’s just what’s declared).

Dharavi may be poor, but it sits on a prime location as far as property developers are concerned. Successive waves of politicians have attempted projects to move the slum’s residents into new housing, and allow private businesses to move in.

Ballaji, 24, works in the family trade, making flower chains for weddings and other celebrations. He has a six-week old son and is keen that his young family have a secure future. He is dismissive of the politicians who come for their votes. He said the election period is the only time government workers come to help clear the rubbish from inside the slum.

“The politicians ask them to clean up during the election,” said Ballaji. “That is to show them they are doing something, so they can get enough votes from people.”

Ballaji said he did see one politician visit the slum in the run up to the vote, but it was the first he had ever seen her. He didn’t even know who she was. “She was walking around the area,” he said. “I don’t know why she came here, maybe to gather our votes. I saw her only that time.

“Maybe I’ll see her again — maybe after five years.” he added.

Ballaji also works as a slum tour guide. He loves Dharavi, and spends his time showing tourists the richness of the community and its entrepreneurial ethos. But he had few kind words for politicians and developers.

“The government talks about a lot of development projects but we don’t see any proper development here,” he said. “Now we’ve just finished with the election, let’s see — maybe we’ll get the same government or maybe a different government. We are not sure what the government is going to do. Let us see.”

Ballaji said that times were hard for many of those trying to make a living in the slum. His flower business was no longer blooming.

“Business is going down. Nowadays no one wears flowers in their hair,” he said.

“India, of course, is growing, but I don’t know where the money is going. The poor are still struggling. We don’t have proper facilities.”

He added, “I think the money is growing in the politicians’ bank accounts.”

But Ballaji wants to stay in Dharavi with his family, as it has everything he needs. For him, the slum development schemes touted by politicians would just mean him being uprooted from his community.

“The new generation will never look for government support,” he said. “The government is not going to do anything, nothing for us. We work hard to do better.”

Photo: Jon Hurd on Flickr

This story was also published on WoNoBo.com, our media partner.

Why Baroda’s queen mother prefers Modi to Rahul

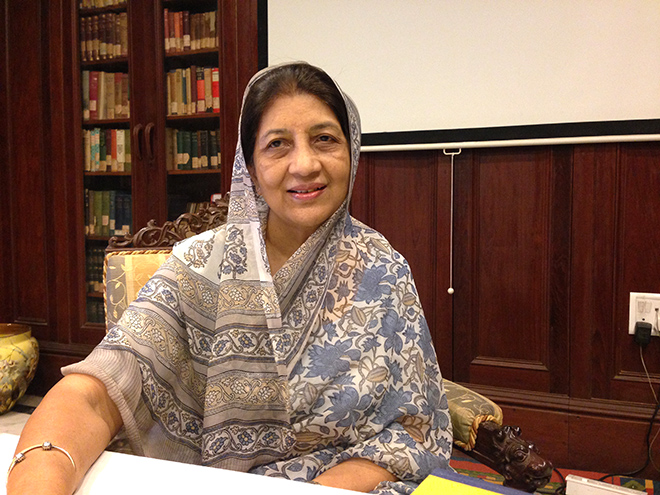

This is the home of Shubhanginiraje Gaekwad, the rajmata (queen mother) of Baroda. After a long hiatus, she has made a political comeback as one of those who proposed Gujarat chief minister Narendra Modi’s candidature for the Lok Sabha constituency of Vadodara.

We wait in a large room adorned with paintings of royals past, piles of books and a chandelier fitted with energy-saving bulbs. After a while we are invited into a bookcase-lined room to meet the rajmata, who sits at the head of a long table, her iPhone in front of her. On the wall is an old map of what was once the kingdom of Baroda, one of the wealthiest princely states, whose Maratha monarchs were among just five Indian rulers accorded a 21-gun salute by the British Raj.

Shubhanginiraje’s husband, the late maharaja Ranjitsinh Pratapsinh Gaekwad, was known for his passion for the arts and cricket and for his paintings. He was also elected twice (1980, 1984) to the Lower House of Parliament on a Congress ticket. The rajmata herself contested the Lok Sabha elections twice, once as an independent candidate in 1996 in Baroda and again as a Bharatiya Janata Party candidate in 2004 from next-door Kheda but without success. She speaks to Patrick Ward on Modi, Gujarat, communalism and Rahul Gandhi.

Does your nomination of Narendra Modi mark another attempt to enter the political fray? If so, why now?

I don’t know. When Mr Modi decided he would like Baroda to be his constituency, I was one of the persons he asked and I agreed because I am glad we are getting someone like him to represent us.

I am supporting the BJP for these elections. The people of Baroda don’t forget us. They still remember us.

Why did he ask you and why did you agree?

I can’t say why he asked me. Probably he wanted my family’s support. He wanted people from all walks of life to support him and I am not his only proposer. Also, I think he wanted to pay respect to our family and the work done by them. You talk to people in town and they still remember the good administration they received during the reign of the Gaekwads. This was during British India, of course.

Modi comes from a small place called Vadnagar, which was part of the old Baroda state. Baroda state was quite extensive, disjointed and vast. It wasn’t easy to administer the entire area, but it was still well done. At that time, only Baroda achieved cent per cent primary education for every child in the state. So, I guess, he wanted to emphasise that because he said, ‘I am a product of that. I received education in a small village because I was part of Baroda state.’

I appreciate Modi because of the credit he gave. Most often, people want credit for themselves. So I appreciate it when someone like him in his position thought of giving due credit. No one would have thought about it if he didn’t mention it. No one would have missed it. This is something from over 100 years ago. Did you know that there was a book published in the times of Maharaja Sayajirao about learning the ropes of good administration? Modi actually got it translated into Gujarati and English and gives it to all his administrative staff. “I give this book whenever new officers come so they can learn something from it, even how to deal with each other, but they would learn the good administration that prevailed in Baroda state,” he said on the day he signed his nomination papers. In a six-minute speech to talk about this for 3-4 minutes is quite telling.

There’s talk he might win both Vadodara and Varanasi and will have to choose between them. If he gives up the Vadodara seat, would you or your son Samarjitsinh be interested in contesting the by-election?

That is for the party to decide. I have no idea just now. I might consider it if they think it is the right thing to do.

Most often, when royalty enters the political fray in India, they do very well. Why were you unsuccessful in those initial rounds?

Once I stood as an independent, so that was a little tricky because there are two big parties against you. Voters were also fewer in number and I remember the race was neck to neck. I got exactly one-third votes. The Congress candidate, who won that year, only won by a margin of 17 votes. It was all last minute and not much preparation had been done. There was also a lot of confusion.

Most people always associated my husband with the Congress. That year, the Congress fielded a candidate with the same last name — Gaekwad. This got people confused in the rural areas. Today, things are a lot better; voters are smarter, more educated.

The next time I stood as a BJP candidate, but I didn’t stand from Baroda, unfortunately. I stood from Kheda, a stronghold of the Congress. The sitting MP was there for two terms, and I told the party I was not at all keen, because I knew I was stepping into a disaster. At that time, (Atal Bihari) Vajpayeeji personally requested me and I got pressured. I said, “I think I’m going to lose, but because you telling me to stand, I will do so.” So I went and followed my party’s orders.

Are you politically active? Do you attend party meetings?

No, I haven’t been very active since. When I stood independently, my husband had left the Congress. Before that he was not active and was totally disillusioned with the party. But having been in the party, he didn’t want to go and join another party. His temperament was not to jump from one party to the other. So he left the party. Otherwise he wouldn’t have canvassed for me.

He did more campaigning for the BJP later. He even campaigned for the BJP candidate in Baroda.

After (former prime minister) Rajiv Gandhi was assassinated, which was tragic, things changed. I think when (Congress president) Sonia Gandhi joined the party, he became totally disillusioned. Your worth in the party was just how much you could please some people. He said, “I can’t do those things.”

Why do you think the BJP is a good option?

They are a good option. What other choice do we have? Surely we can’t have (Congress vice-president) Rahul Gandhi? What are his credentials? He hasn’t proved himself by being a minister in a Cabinet, he hasn’t done a day’s job in his life. He hasn’t proved himself in any task. I feel, as a young man, one at least ought to go out and earn one’s living. All our young boys and girls are working so hard. But look at him. Here he is, a young fellow, accept him as prime minister. Why? What has he done?

Our country is so very diverse and complicated. It is not the same, every part is different. You need someone to have thought about these things deeply. Someone who is mature, and it is not just his age that’s an issue. Some people do their best at a young age. But he has done nothing.

Can Modi reproduce what he has done in Gujarat across the country?

He can try. At least you have a man who has sincerity of purpose and does his best. He has been working hard for the past 12 years in Gujarat. At least he’ll try his best. He is from the grassroots, he knows what is life, he has seen that. In all areas of Baroda constituency, he will definitely do very well. I am sure he is going to win, there is no doubt about that. I am sure he has already gauged that, which is why he has come here to a seat he was sure to win. He knew he was not going to devote much time to Baroda constituency, or any constituency in Gujarat for that matter. So, obviously, he was looking for a safe seat. He is concentrating on all parts of the country now, how much can he be here?

He is a good choice. They need someone who has drive, who has charisma, who can attract people with his talking. As a prime minister, Manmohan Singh is educated, probably much more educated than Modi, but he could not make a good prime minister, people never related to him. And then, of course, there were these two power centres, which was so pathetic.

It’s disgraceful, the office of our prime minister has been degraded thanks to the Congress president. Once a person is on that chair, we have to respect that chair.

What should Modi’s priority be should be become prime minister?

It should be to bring efficiency to the administration because the common man suffers because people who should be doing their job, don’t. Especially in government offices, applications should be dealt with in a swifter manner. People should be tended to, but people don’t do their job.

Also, great reforms need to be introduced in our judicial system. People wait for years to seek justice, but even after 40, 50 years, they don’t get it.

Lastly, a lot of attention has to be paid to infrastructure.

What about communalism?

Some people keep talking about it because they don’t want the people to forget about it. People just want to let it be, forget it and carry on with their lives. Everybody wants to move on. The youth is not bothered. They want jobs, they want to earn a living, they want infrastructure.

Communalism is always raised as an issue by politicians. They want to make an issue where there is no issue. I don’t deny that it is an issue, but it is prevalent all over the country. It is not like Gujarat has more of it than any other part of the country.

No doubt, what happened in Gujarat was sad, but the Congress government at the Centre has always harped on this as this is easy for them. They want to keep it fresh in people’s minds so that people outside the state believe the situation is worse that what it is.

We have had communal riots in Gujarat for many years. Even when my husband was in Parliament we had problems, but it was instigated by some local goons. When there is a Hindu festival, there is a problem and vice-versa. These situations are just manipulated most of the time.

So you think the Congress raising the issue can create divisions?

Exactly. What was the need for (Congress president) Sonia Gandhi to call the imam of Delhi to her office and tell him, “Please tell all the Muslims to vote for the Congress”? You can’t do that. You may tell him in private, that’s all right, but you can’t call him and tell him and make an official statement on television. This means you are already dividing the country and its people.

Why are you dividing them on the basis of religion? Let anyone vote for the Congress, let anyone vote for the BJP.

What about the hate speech made recently by Vishwa Hindu Parishad leader Pravin Togadia?

There are a few people like that, talking rubbish. But there are people like that on all sides. You can’t go on controlling the way people talk and elections only make people fiercer in their speeches. Politicians talk like that to divide the people, but as a party, the BJP has not tried to do that. Modi has tried to bring people together. The Congress, on the other hand, has only tried to appease the minorities, especially the Muslims, which I don’t agree with. Why appease them? Why aren’t there the same rules for everybody? Why can’t they follow the law of the land? This only makes other people irritated about the situation, causing an anti-Muslim vibe. This is the policy of the government, which benefits a few people.

This interview was also published on Rediff.com, our media partner.

Photos: Vaiyhaysi P Daniel/Rediff.com